It is the third most common type of skin cancer after basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). In New Zealand is the fourth most common reported cancer overall.

MM can invade into the surrounding tissues and spread to regional sites. About 4-8% of them spread (metastasise) to distant sites of the body. Melanomas are primarily treated by surgical removal. More advanced melanomas are also treated with medications.

Melanoma: The Definitive Guide

In this article we go further than most pages on MM, providing you with answers to commonly unanswered questions. This includes:

- Why does surgery for melanoma result in such a large scar?

- Why is surgery for melanomas routinely done in two steps?

- What does the pathology report mean and what are the most important components of the report?

- How much higher risk do blondes and red-heads face for developing MM? (Hint: it is a lot).

- Are prostate cancer and endometriosis risk factors?

- Tanning releases endorphins, does that mean that it is an addiction?

- Does Viagra increase your risk?

How common is melanoma (Epidemiology)?

In New Zealand, there were 2,730 melanomas (55 / 100,000 population) diagnosed during 2019. Different countries have markedly different rates.

While it’s generally more common in regions closer to the equator, this only holds true for individuals with fair skin. Darkly pigmented people do not have higher rates of MM in lower latitude regions.

| Country | Incidence (per 100,000) |

| New Zealand | 55 |

| Australia | 63 |

| United States | 27 |

| Europe | 15 |

Melanoma rates are continuing to increase mostly in people over the age of 40 whereas rates among younger people are declining. This is likely to be due to better sun protection education during their lifetimes. Overall, the mortality rate is declining, probably due to earlier detection.

Melanomas are approximately 20% more common amongst men, compared to women. Presumably, this is because of better sun protection behaviours by women.

Who gets melanoma (risk factors)?

Sun exposure is by far the most important risk factor for developing melanomas. Ultraviolet radiation causes damage to the DNA in the skin and over time this can progress to developing MM.

Most other individual risk factors are a function of sun exposure which includes lifestyle, occupational sun exposure, fair skin, and older age.

- Intermittent, intense sun exposure and sunburns are the most important risk factors for the development of melanoma. However, high chronic exposure also appears to contribute.

- The intermittent, intense pattern appears to be more important for areas with occasional exposure, e.g., the back and legs.

- High chronic and occupational sunlight exposure is most important for melanomas of the head and neck.

- In 2009, the World Health Organisation (WHO) classified tanning beds as a Group 1 Carcinogen (the same grouping as cigarette smoking). Several studies have shown that tanning beds confer an increased risk of melanoma and for some groups, their risk is more than six-fold.

- Fair skin increases the risk of development by about three times overall. Hair colour is a proxy for fair skin:

- Blondes have a 2 times increased risk.

- Redheads are 3.6 times more likely to develop.

Viagra

Various studies have suggested a link between sildenafil (Viagra) and melanoma, reporting an increased risk of 14-84%. However, most of these studies did not control for lifestyle factors e.g., sun exposure, medical conditions, etc. We are not convinced by this association.

Endometriosis

Some small studies have also seen an increase in those with endometriosis (60% increase) and prostate cancer (83% increase), however further studies are required to confirm the association.

While only 29.1% of melanomas develop from existing naevi (moles), having many naevi increases the risk.

- 16 naevi: 47% increased risk.

- > 100 naevi: 600% increased risk.

A family history also increases the risk:

- One first-degree relative with melanoma results in about a three-times risk.

- Two first-degree relatives with melanoma confer a 9-times risk for an individual developing melanoma.

Another melanoma risk factor is having previously had one:

- One previous melanoma results in a 2-3 times risk of developing another.

- Two melanomas result in a 72% risk of developing another within 5 years.

Some common risk factors are summarised in the following table:

| Risk factor | Relative Risk |

| Previous melanoma | 2-3 |

| Previous NMSC | 4.3 |

| 1+ parent | 2.4-4.4 |

| Sibling | 3-4.4 |

| Two first degree relatives | 8.9 |

| Naevi 0-15 | 1.0 |

| Naevi 16-40 | 1.5 |

| Naevi 41-100 | 2.2-4.7 |

| Naevi 101-120 | 6.9 |

| Red hair | 3.6 |

| Blond hair | 2 |

| Transplant recipient | 3.6 |

| Moderate alcohol | 1.2 |

Immunosuppression

Those who are chronically immunosuppressed have an increased risk of developing melanoma. Transplant recipients have 3.6 times increased risk.

Diet

Several studies have reported protective or harmful associations with melanoma (caffeine, citrus fruit). However, these studies have not completely controlled for confounding factors so it is difficult to draw meaningful conclusions.

How does a melanoma develop (Pathogenesis)

Melanomas develop from a complex interaction of genes and environmental influences, in particular UV-induced DNA damage.

It is important to realise that even tanning (without burning) results in UV-induced damage of keratinocyte DNA damage and induction of p53-mediated stimulation of melanocytes (pigment cells). Interestingly, this process involves the proopiomelanocortin (POMC)/melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) which contains endorphins, leading to the hypothesis that this could be a pathway for sun addiction.

Almost all melanomas develop through activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. This pathway promotes cellular growth and survival. Mutations in several of these proteins and receptors can lead to uncontrolled cellular growth and development. In melanomas, the most common are mutations affecting BRAF (45%) and NRAS (18%).

Understanding this pathway has resulted in the development of several medical medications (small molecule inhibitors) targeting BRAF, MEK, and KIT mutations. Inhibitors of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) are currently in development.

Symptoms & appearance of melanoma (clinical features)

Melanomas can develop anywhere on the skin – even where the sun doesn’t shine! But it usually develops in areas exposed to the sun. In those with darkly pigmented skin, melanomas are actually more common in non-sun-exposed areas. It is important to realise that two-thirds arise de novo (without an indefinable preceding naevus).

The ‘ugly duckling’ sign describes the observation that most people with numerous moles have a few signature naevus types. The ugly duckling lesion that is different from the others should be considered suspicious.

Adjusted for surface area, the face, head, and neck are the most common sites for MM, followed by the trunk.

Subtypes of melanoma

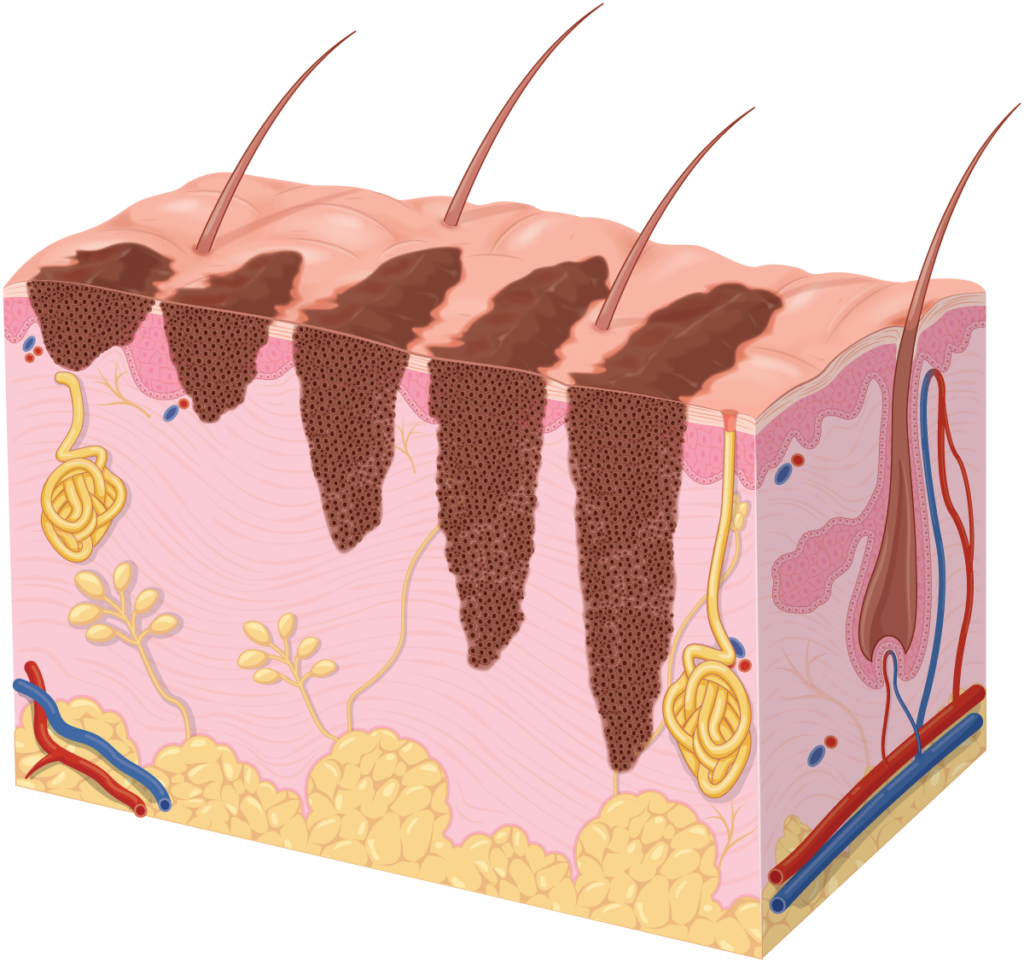

Melanomas mostly develop as superficial lesions of the epidermis (top layer of skin) and can remain as such for several years. This is known as the radial or horizontal growth phase.

Once melanomas invade the dermis, they enter their vertical growth phase which also gives them the potential to spread to distant sites (metastasise). Some (nodular) melanomas start with a vertical growth phase and as a result, are considered more aggressive. The strongest predictor of metastasis is the (Breslow) depth of the tumour.

- Superficial spreading makes up about 70% of melanomas with 60% being diagnosed with a Breslow thickness of ≤ 1 mm and therefore highly treatable. Classically they appear as dark macules or patches, irregular borders, and potentially different colours.

- Nodular comprise about 15% of melanomas and typically appear as dark papules or nodules. Most nodular melanomas are already > 2 mm at the time of diagnosis.

- Lentigo maligna makes up about 10% and usually appears in older people with chronic sun damage. It typically presents as a dark macule or patch that grows over years.

- Acral lentiginous comprise less than 5% of melanomas but is the most common type in those with darker skin. They appear on the palms and soles of the hands and feet as well as underneath the nail (subungual). They appear as dark macules or patches.

- Amelanotic lack pigment and make up about 2% of cases. Any of the above subtypes can present as an amelanotic melanoma. They can present as pink, red, or flesh-coloured macules, papules or nodules making them very difficult to detect.

- Spitzoids are uncommon and they usually present as a papule or nodule that is either red or dark in colour.

- Desmoplastics are also rare and typically located in areas of chronic sun exposure. They present as an amelanotic nodule or scar.

- Melanocytomas are rare darkly pigmented and slow-growing nodules.

ABCDE criteria for melanoma

A number of scoring systems have been proposed to assist with screening and identifying an MM, particularly for laypeople or non-specialists. These are the ABCDE criteria and the Glasgow seven-point checklist. The ABCDE Criteria are the most widely used.

These criteria may help with the identification. They are mostly applicable to superficial spreading MM and less so to other subtypes.

- Asymmetry.

- Border irregularity.

- Colour variation, ie different colours or shades through the lesion.

- Diameter ≥ 6 mm.

- Evolution – the lesion is changing size or shape.

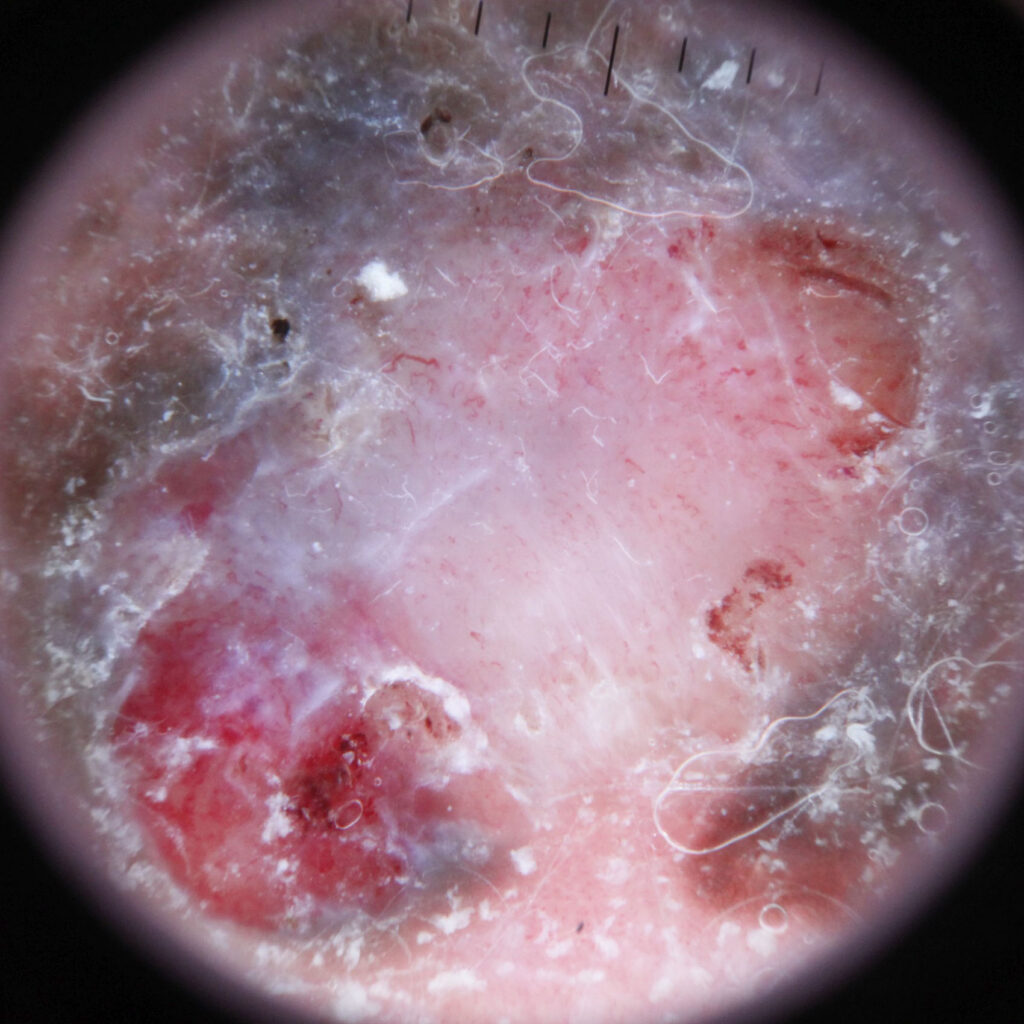

Dermoscopy helps with the diagnosis of melanoma.

Specialist dermatologists tend not to use these criteria and rely more on pattern recognition as they are able to draw from their extensive experience. Furthermore, they will also often use dermoscopy to assist with diagnosis.

How is a melanoma diagnosed?

All suspected melanomas should have confirmation by laboratory analysis (histology) which involves a surgical procedure to obtain the tissue sample. In most situations, an excisional biopsy should be performed – meaning the entire lesion is surgically removed with a narrow (2 mm) margin. While this may seem redundant, full lesion sampling is the standard recommendation to avoid the risk of a sampling error which can occur when taking a small (partial) biopsy.

Sampling errors arise when a biopsy is taken from a small part of the lesion. The analysis could be reported as benign when the biopsy has simply missed the melanoma. This is one of the worst errors to occur as the patient may avoid getting the lesion checked again while it continues to grow as they have been falsely reassured that it is benign.

However, in very large or difficult lesions an incisional biopsy can be performed with care. This should ideally be taken across a full diameter of the lesion and include the most significant area to minimise the risk of a sampling error.

After the biopsy, the sample is fixed in formalin, stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and prepared on slides. The pathology team may use a range of immunohistochemical stains to help confirm the diagnosis.

The pathologist will then examine these slides under a microscope and issue their report. There is no single diagnostic feature of melanoma. The diagnosis is made from a combination of characteristics. Often the diagnosis is straightforward, however, it can be difficult in some cases which results in an amount of pathologist discordance. Difficult-to-diagnose cases may require special immunohistochemical stains or molecular techniques to determine the diagnosis. This can delay the biopsy results, but the delay should not be interpreted as bad news.

The pathology report

The pathologist will issue a report to your doctor about your melanoma. This should include the following information:

- The diagnosis. Sometimes the pathologist may not be able to make a definitive diagnosis. They may make a statement like:

- “Melanoma can not be ruled out.”

- “Suspicious for melanoma.”

In this situation, the dermatologist will need to make a clinical judgement, but in most situations, they will recommend treatment as if the lesion is a melanoma. They will recommend surgical removal because it was clinically suspicious and leaving a possible MM could be catastrophic.

- Excision margin or if the margin was involved.

All other information in the report is essentially about risk stratification to assist with treatment planning:

- Breslow thickness: this is the single most important prognosticator and at a minimum determines how wide the subsequent formal excision margin should be.

- Ulceration: present/absent.

- Mitoses: number per mm squared. This is a measure of how rapidly the cells are dividing/replicating resulting the tumour growth.

- Microscopic satellites: present/absent.

- Vascular invasion: present/absent.

- Clark level: this is the anatomical level of invasion:

- Level 1: Confined to the epidermis: in situ melanoma.

- Level 2: Invasion into the papillary (superficial) dermis.

- Level 3: Invasion to the junction of the papillary and reticular dermis.

- Level 4: Invasion into the reticular dermis.

- Level 5: Invasion into the subcutaneous tissue (fat).

Staging

Staging provides information on how extensive an MM has spread. It determines whether it is still in the skin (local) as spread to the nearest body region or to distant sites (metastatic). This information is then used to determine what treatment is appropriate.

It is important to realise that not all melanoma diagnoses require a complete staging work-up. This would potentially lead to a lot of unnecessary investigations and in particular unnecessary radiation exposure from scans.

Staging workup

Further imaging is recommended for tumours with a score of ≥ T3b (Breslow > 2mm with ulceration). Depending on the clinical situation, this may include:

- CT chest, abdomen, pelvis, or PET-CT.

- For tumours of the head and neck a CT neck.

- Stage IIIC or IIID an MRI of the brain.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

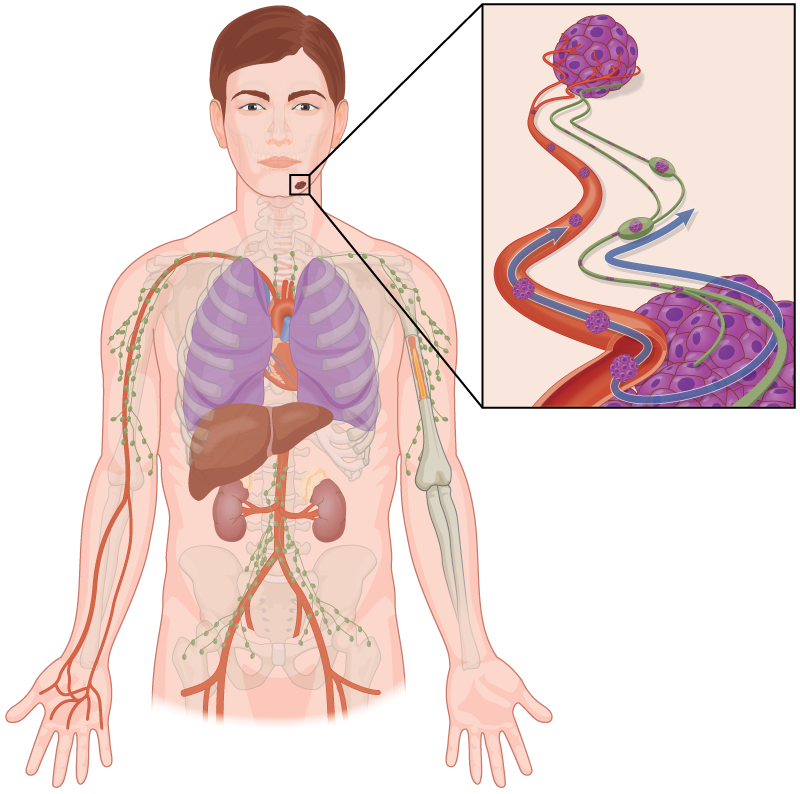

Sentinel lymph node biopsies (SLNB) have been used to test for the microscopic spread of melanoma to the nearest (sentinel) lymph node. The procedure involves injecting a radioactive tracer to identify the first draining (sentinel) lymph node. This sentinel node is removed and sent for analysis to determine if it contains MM.

The theory is that if detected early, more aggressive treatments may result in better survival outcomes. Unfortunately, the study results have conflicted outcomes and treatments such as complete removal of the regional lymph nodes have not shown a survival benefit. Furthermore, some lymph node-positive patients may not be eligible for more aggressive treatments and some SLNBs are still often discussed as an option.

TNM staging system

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) system is used to score melanoma risk information and this is collated to classify according to the AJCC prognostic stage group.

| T category | Thickness | Ulceration status |

| Tx: Thickness unknown | N/A | N/A |

| T0: No primary | N/A | N/A |

| Tis (in situ) | N/A | N/A |

| T1 | ≤ 1.0 mm | Unknown |

| T1a | < 0.8 mm | Nil |

| T1b | < 0.8 mm 0.8 – 1 mm | Ulcerated Either |

| T2 | > 1 – 2 mm | Unknown |

| T2a | > 1 – 2 mm | Nil |

| T2b | > 1 – 2 mm | Ulcerated |

| T3 | > 2 – 4 mm | Unknown |

| T3a | > 2 – 4 mm | Nil |

| T3b | > 2 – 4 mm | Ulcerated |

| T4 | > 4 mm | Unknown |

| T4a | > 4 mm | Nil |

| T4b | > 4 mm | Ulcerated |

| Node category | Description | In-transit ± micro-satellite metastases |

| NX | Not assessed | No |

| N0 | Nil | No |

| N1 | 1 node or satellite/transit | |

| N1a | 1 microscopic | No |

| N1b | 1 clinical | No |

| N1c | Nil | Yes |

| N2 | 2-3 nodes or satellite/transit | |

| N2a | 2-3 microscopic | No |

| N2b | 2-3, 1+ clinical | No |

| N2c | 1 | Yes |

| N3 | 4+ nodes or satellite/transit | |

| N3a | 4+ microscopic | No |

| N3b | 4+, with 1+ clinical | No |

| N3c | 2+ | Yes |

| M category (M) | M criteria (metastasis location) |

| M0 | Nil metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis present |

| M1a | Distant skin, muscle, nodes |

| M1b | Lung |

| M1c | Non-CNS viscera |

| M1d | CNS |

Prognostic stage

Once a TNM score is determined, this will be used to determine the prognostic stage. An abbreviated staging score provides general information.

| Stage | Description |

| 0 | In situ |

| 1 | < 2 mm Breslow |

| 2 | > 2 mm Breslow or > 1mm with ulceration |

| 3 | Regional lymph node involvement |

| 4 | Distant metastatic spread |

However, specialists will often use the full AJCC prognostic staging system:

| N | M | Stage | Workup | |

| Tis | N0 | M0 | 0 | Nil |

| T1a | N0 | M0 | IA | Nil |

| T1b | N0 | M0 | IA | Nil |

| T2a | N0 | M0 | IB | Nil |

| T2b | N0 | M0 | IIA | Nil |

| T3a | N0 | M0 | IIA | Nil |

| T3b | N0 | M0 | IIB | CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| T4a | N0 | M0 | IIB | CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| T4b | N0 | M0 | IIC | CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| T0 | N1b, N1c | M0 | IIIB | CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| T0 | N2b, N2c, N3b, or N3c | M0 | IIIC | CT CAP or PET-CT, MRI brain |

| T1a/b-T2a | N1a or N2a | M0 | IIIA | CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| T1a/b-T2a | N1b/c or N2b | M0 | IIIB | CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| T2b/T3a | N1a-N2b | M0 | IIIB | CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| T1a-T3a | N2c or N3a/b/c | M0 | IIIC | CT CAP or PET-CT, MRI brain |

| T3b/T4a | Any N ≥N1 | M0 | IIIC | CT CAP or PET-CT, MRI brain |

| T4b | N1a-N2c | M0 | IIIC | CT CAP or PET-CT, MRI brain |

| T4b | N3a/b/c | M0 | IIID | CT CAP or PET-CT, MRI brain |

| Any T, Tis | Any N | M1 | IV |

Treatment

Surgery

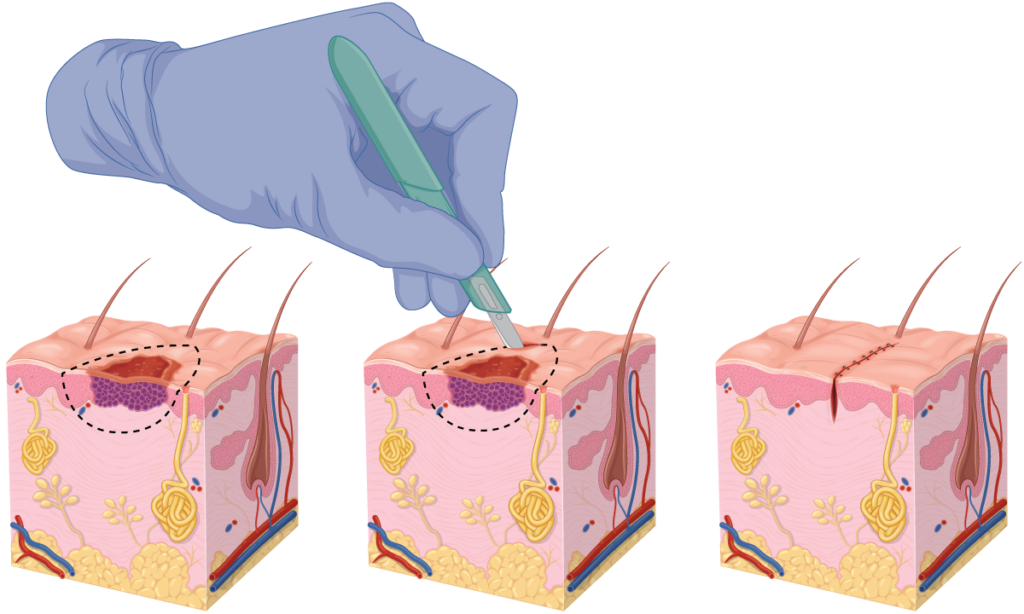

Surgery is an essential part of treatment as it provides diagnostic and staging information. Optimal treatment will require surgery to clear the tumour. While an excision with clear margins may have been achieved with the excisional biopsy, narrow margins are not considered adequate.

It is important to realise that histological analysis is not 100% accurate and the method used does introduce some uncertainty. Clear margins on a pathology report do not necessarily mean that the melanoma has been completely removed. We explain this further on our wide local excision (WLE) page.

Numerous national guidelines recommend further excision with wide margins to minimise the risk of recurrence or distant metastatic spread. These margins are determined by consensus and are partly based on previous studies comparing surgical margins with patient outcomes. In New Zealand, the recommended margins are described below:

| Tumour score | Breslow thickness | Margin |

| Tis | (in situ | 5 – 10 mm |

| T1 | ≤ 1 mm | 10 mm |

| T2 | 1-2 mm | 10-20 mm |

| T3/T4 | > 2mm | 20 mm |

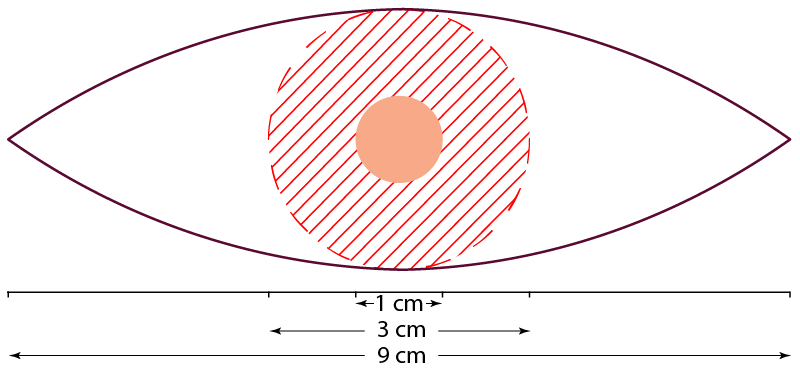

A wide local excision (WLE) is normally performed under local anaesthetic. The surgeon marks out the surgical site based on the previous scar (from the biopsy). The margins are determined from the above table and the excision is performed down to at least the fascia (the fibrous layer below the subcutaneous fat). The incision will be made in a 3:1 ellipse around this safety margin. So, a thin melanoma with a 1 cm diameter will result in a scar line approximately 9 cm long. On cylindrical areas e.g., the arm, the ratio may be 5:1, meaning a scar line of about 15 cm.

Mohs Surgery

In some situations, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is sometimes performed on melanoma in situ of the head and neck although this is not routine.

Advanced stage melanomas

It is difficult to outline treatment options for advanced-stage melanomas (metastatic spread) as different jurisdictions and medical insurance companies will have different treatment options and eligibility criteria.

Furthermore, treatment regimens are normally tailored on a case-by-case basis. Some of these treatments may be used in combinations. We provide this information as a general information source for those who are interested:

- Surgical metastectomy is the surgical removal of metastases when there is a low burden of metastatic disease.

- Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy with PD-1 inhibitors: pemrolizumab, nivolumab.

- BRAF inibitors: dabrafenib and vemurafenib.

- MEK inhibitors: trametinib.

- c-KIT inhibitors: imatinib.

- Radiation therapy.

Surveillance

The objective of surveillance is to identify:

- New melanomas early.

- Local or regional recurrences that could be curable.

- A metastatic disease that can be treated with systemic therapies.

Surveillance regimens vary somewhat but in essence, higher risk/stages tend to have more frequent follow-up regimens:

- All patients should undertake a regular self-skin examination.

- Stage I & IIA: Every six months for two years, then annually for life.

- Stage IIB & III: Every four months for two years, every six months for five years, then annually for life.

Prognosis

People have an increased chance of developing a second melanoma. The risk is about 3-8 times the general population. About 8% will develop a second one within five years of the initial diagnosis.

The concern is the potential for metastatic spread which is life-threatening. It is important to realise every individual case is unique. We provide the following information as a general guide for those who desire this information. However, we must emphasise that it is just a guide.

New medications and treatments are becoming available all the time and this will of course have an impact on these details. Furthermore, the survival rates below are averages, there will be individuals who may have Stage IV disease but are otherwise very fit and healthy who survive longer than someone with Stage III disease but has many co-morbid medical conditions.

| Stage | 5-year survival |

| Localised (Stage I & II) | 99% |

| Regional (Stage III) | 68% |

| Distant (Stage IV) | 30% |

Prevention

The main approach to prevention involves sun protection. Some studies have suggested that rigorous sun protection during childhood can reduce the development of melanomas by 78%, but this level of reduction has not yet been conclusively proven.

Daily sunscreen use has been shown to reduce the development of melanomas by 50-73%. Obviously, daily sunscreen use requires a significant commitment from individuals. Even dermatologists are not perfect with their sun protection.

General sun protection advice includes:

- Avoiding sunburn and intentional tanning.

- Wearing sun protective clothing (hat, sunglasses, etc).

- Seeking shade where available.

- Taking extra care in highly reflective environments e(water, snow, and sand).

- Obtaining vitamin D through food and supplements if need be.

- Using a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen with a minimum SPF of 50+. Apply it 15-30 minutes prior to sun exposure and reapply every 2 hours or after sweating, swimming, or rubbing.

We have separate pages dedicated to sun protection and sunscreen. These pages cover controversial topics such as the impact of vitamin D, high-SPF sunscreens, and the absorption of sunscreen ingredients.

Other resources

References

- Ministry of Health. New Cancer Registrations 2019. Ministry of Health Website, New Zealand Government, accessed 15 August 2022, www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-cancer-registrations-2019

- Stang, A., Khil, L., Kajüter, H., et al. (2019). Incidence and mortality for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: comparison across three continents. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 33(S8), 6-10. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15967

- Abroms L, Jorgensen CM, Southwell BG, et al. Gender differences in young adults’ beliefs about sunscreen use. Health Educ Behav. 2003 Feb;30(1):29-43. doi: 10.1177/1090198102239257

- McCarthy, W. H. (2004). The Australian experience in sun protection and screening for melanoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 86(4), 236-245. doi: 10.1002/jso.20086

- Eide MJ, Weinstock MA. Association of UV index, latitude, and melanoma incidence in nonwhite populations–US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, 1992 to 2001. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:477. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.4.477

- Baade P, Coory M. Trends in melanoma mortality in Australia: 1950-2002 and their implications for melanoma control. Aust N Z J Public Health 2005; 29:383. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00211.x

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case-case-control study. Br J Cancer 2006; 94:743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602982

- Nelemans PJ, Groenendal H, Kiemeney LA, et al. Effect of intermittent exposure to sunlight on melanoma risk among indoor workers and sun-sensitive individuals. Environ Health Perspect 1993; 101:252. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101252

- Elwood JM, Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Pearson JC. Cutaneous melanoma in relation to intermittent and constant sun exposure–the Western Canada Melanoma Study. Int J Cancer 1985; 35:427. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910350403

- Gandini S, Montella M, Ayala F, et al. Sun exposure and melanoma prognostic factors. Oncol Lett 2016; 11:2706. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4292

- Lazovich D, Isaksson Vogel R, Weinstock MA, et al. Association Between Indoor Tanning and Melanoma in Younger Men and Women. JAMA Dermatol 2016; 152:268. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.2938

- Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: III. Family history, actinic damage and phenotypic factors. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41:2040. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.03.034

- Kvaskoff M, Mesrine S, Fournier A, et al. Personal history of endometriosis and risk of cutaneous melanoma in a large prospective cohort of French women. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:2061. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2061

- Li WQ, Qureshi AA, Ma J, et al. Personal history of prostate cancer and increased risk of incident melanoma in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:4394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1915

- Pampena R, Kyrgidis A, Lallas A, et al. A meta-analysis of nevus-associated melanoma: Prevalence and practical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77:938. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.149

- Swerdlow AJ, English J, MacKie RM, et al. Benign melanocytic naevi as a risk factor for malignant melanoma. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986; 292:1555. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6535.1555

- Begg CB, Hummer A, Mujumdar U, et al. Familial aggregation of melanoma risks in a large population-based sample of melanoma cases. Cancer Causes Control 2004; 15:957. doi: 10.1007/s10522-004-2474-2

- Hemminki K, Zhang H, Czene K. Familial and attributable risks in cutaneous melanoma: effects of proband and age. J Invest Dermatol 2003; 120:217. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12041.x

- Chen T, Fallah M, Försti A, et al. Risk of Next Melanoma in Patients With Familial and Sporadic Melanoma by Number of Previous Melanomas. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151:607. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.4777

- Wehner MR, Linos E, Parvataneni R, et al. Timing of subsequent new tumors in patients who present with basal cell carcinoma or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151:382. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3307

- Hollenbeak CS, Todd MM, Billingsley EM, et al. Increased incidence of melanoma in renal transplantation recipients. Cancer 2005; 104:1962. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21404

- Fisher DE, James WD. Indoor tanning–science, behavior, and policy. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:901. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1005999

- Omholt K, Platz A, Kanter L, et al. NRAS and BRAF mutations arise early during melanoma pathogenesis and are preserved throughout tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9:6483. doi: aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/9/17/6483/202291/

- Albino AP, Le Strange R, Oliff AI, et al. Transforming ras genes from human melanoma: a manifestation of tumour heterogeneity? Nature 1984; 308:69. doi: 10.1038/308069a0

- Ball NJ, Yohn JJ, Morelli JG, et al. Ras mutations in human melanoma: a marker of malignant progression. J Invest Dermatol 1994; 102:285. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371783

- Pampena R, Kyrgidis A, Lallas A, et al. A meta-analysis of nevus-associated melanoma: Prevalence and practical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77:938. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.149

- Youl, P. H., Janda, M., Aitken, J. F., Del Mar, C. B., Whiteman, D. C., & Baade, P. D. (2011). Body-site distribution of skin cancer, pre-malignant and common benign pigmented lesions excised in general practice. British Journal of Dermatology, 165(1), 35-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10337.x

- Hassel JC, Enk AH. Melanoma. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology, 9th Edition, Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al (Eds), McGraw-Hill Education, 2019. Vol 1, p.1982.

- Demierre MF, Chung C, Miller DR, Geller AC. Early detection of thick melanomas in the United States: beware of the nodular subtype. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:745. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.745

- Beroukhim K, Pourang A, Eisen DB. Risk of second primary cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma after cutaneous melanoma diagnosis: A population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82:683. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.024

- Pomerantz H, Huang D, Weinstock MA. Risk of subsequent melanoma after melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma: a population-based study from 1973 to 2011. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 72:794. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.006

- Stern RS, Weinstein MC, Baker SG. Risk reduction for nonmelanoma skin cancer with childhood sunscreen use. Arch Dermatol 1986; 122:537. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1986.01660170067022

- Green AC, Williams GM, Logan V, Strutton GM. Reduced melanoma after regular sunscreen use: randomized trial follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:257. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.7078

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

- Leiter, U., Stadler, R., Mauch, C., Hohenberger, W., Brockmeyer, N. H., ‘¦ Berking, C. (2019). Final Analysis of DeCOG-SLT Trial: No Survival Benefit for Complete Lymph Node Dissection in Patients With Melanoma With Positive Sentinel Node. Journal of Clinical Oncology, JCO.18.02306. doi: 10.1200/jco.18.02306

- Faries, M. B., Thompson, J. F., Cochran, A. J., Andtbacka, R. H., Mozzillo, N., Zager, J. S., ‘¦ Beitsch, P. D. (2017). Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(23), 2211-2222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613210

Related Posts

-

Does Nicotinamide Help with Skin Cancer?

An in-depth review of the evidence for and against supplementing with nicotinamide in an effort to reduce the risk of developing skin cancer.Read more

-

What a Mohs Surgeon sees under the Microscope

Experience matters when it comes to picking out a tumour under the microscope. The Skintel Mohs specialists have viewed more than 10,000 slides and counting! […]Read more

-

Skin Cancer: A Basic Guide

Skin cancer is by far the most common type of cancer. They are most common in areas with lots of sun exposure such as the face, neck, arms, and head.Read more