What is a basal cell carcinoma?

A basal cell carcinoma is a cancerous overgrowth of the basal (bottom layer) cells of the epidermis – the most superficial layer of the skin. BCCs are by far the most common type of skin cancer and the most common type of all cancers, making up about one-third of all cancers worldwide.

Basal Cell Carcinoma: The Definitive Guide

This is The Definitive Guide on Basal Cell Carcinoma. While we cover the topics many other sites discuss, we go more in-depth to look at commonly asked questions that often go unaddressed. We also point out interesting facts along the way, including:

- Why does a doctor choose one treatment over another, and why it can be dangerous to have cryotherapy (freezing) treatment for BCCs.

- Which common medications increase your risk of developing one?

- Why does surgery for a BCC result in such a large scar?

- Are men or women at higher risk for BCCs?

- Why does NZ not record statistics for BCCs?

- How much does alcohol increase your risk of developing one?

- What do hedgehogs have to do with BCCs?

It is rare for BCCs to spread to distant sites of the body (metastasise), but they can cause problems to surrounding structures (locally invasive) such as muscle, bone, and nerves. Although, they are classed as non-aggressive and grow slowly.

They are classified as non-melanoma (keratinocyte) skin cancer (NMSC) and make up about 80% of NMSCs. BCCs have been known by many names including rodent ulcers, epithelioma, and basalioma.

Most BCCs are curable and are typically treated with surgical removal (excision). Less invasive treatments are possible in appropriate situations – particularly if it is early or superficial. Some less invasive treatments include creams (imiquimod) or freezing (cryotherapy).

How common are BCCs (Epidemiology)?

It is difficult to know precisely how common BCCs are as governments generally don’t record statistics for BCCs. As an example, the New Zealand Cancer Registry (NZCR) records all cancers but specifically excludes BCCs (except when they arise in the genitalia). In 1958, The NZCR decided to stop registering BCCs due to resource constraints… there were just too many BCCs!

However, various estimates suggest at least 70,000 (1,400/100,000 population) BCCs will be diagnosed each year in New Zealand (about 2% of the adult population). Different countries have varying rates of skin cancer. In Australia, there are approximately 300,000 (1,168/100,000 population) BCCs diagnosed per year. This compares with about 2.8 million (850/100,000 population) BCCs per year in the United States and a 30% lifetime risk for white Americans. Within the USA, regions closer to the equator have rates of BCCs that are double the northern states.

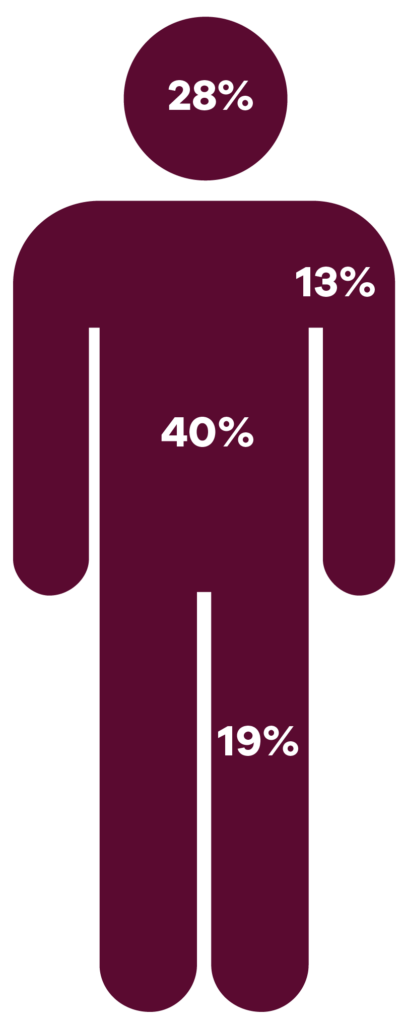

BCCs tend to be more common amongst men, by about 40% compared to women. Presumably, this is partly because of better sun protection behaviours by women.

About 80% of baby boomers with fair skin will develop a BCC in their lifetime.

Who is likely to get a basal cell carcinoma (Risk Factors)?

There is no getting past it, sunlight is a giant carcinogen and is by far the most important risk factor for developing BCCs. Ultraviolet radiation causes damage to the DNA in the skin and over time this can progress to the development of skin cancers. Most other risk factors for BCCs are a function of sun exposure which includes lifestyle, fair skin, older age, number of previous sunburns, etc.

- Childhood sun exposure has a more significant effect than adult exposure. People who have experienced a moderate sunburn before the age of 15 have a 30% higher risk of developing a BCC. Those who suffered a significant sunburn once per year in childhood have a 70% higher risk.

- Intermittent, intense sun exposure has a higher risk compared to lower-dose chronic exposure. This contrasts with chronic cumulative sun exposure for squamous cell carcinomas.

- Fair complexion is a risk factor for developing skin cancer. Individuals with Type I skin (red hair, freckles, and an inability to tan) have a 100% increased risk of developing a BCC. BCCs are very rare in those with dark skin.

- Tanning bed use increases the risk of developing BCCs at an earlier age. Studies have shown that tanning bed users have a 60% higher risk of developing skin cancer prior to the age of 50, and they double their risk if their first use of a tanning bed was prior to the age of 20. However, the risk may not be completely related to sunbed use as sunbed users also sunbathe more often and are less rigorous with sun protection.

The biggest risk factor

One of the biggest risk factors for developing a BCC is having previously been diagnosed with one. About 45% of people will develop another one within five years of a diagnosis. For those with a history of at least two BCCs, their risk is 75% for developing another one within 5 years.

Some medications may increase the risk of BCCs by increasing the skin’s sensitivity to light. These include common cardiac and blood pressure medications. Medications that have been found to increase your risk are listed in the following table:

| Medication | Risk Increase (%) |

| Thiazide diuretics (e.g., hydrochlorthiazide) | 17% |

| Calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, diltiazem, felodipine, nifedipine, etc.) | 15% |

| Beta-blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, esmolol, metoprolol, etc.) | 9% |

| Statins (simvastatin, atorvastatin, pravastatin, etc.) | 0-14% (conflicting studies) |

| Tetracyclines (eg. doxycycline) | 11% |

Radiation exposure e.g., cancer treatment, or occupational exposure may also increase the risk:

- Those who have received a radiation treatment dose of 35 Gray or more (a typical dose) during childhood have a 40 times higher risk of developing BCCs.

- Survivors of the Japanese atomic bombs have a 2-3 times risk.

Genetic Disorders

There are a few genetic disorders that substantially increase the risk of developing BCCs. While these are rare, they have helped our understanding of the pathophysiology of BCCs and highlighted potential therapeutic targets.

- Naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (aka Gorlin syndrome) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder of the human patched gene (PTCH1) where individuals develop numerous BCCs at a young age (average 20 years) as well as developmental abnormalities and other tumours such as odontogenic keratocytes and medulloblastoma.

- Rombo syndrome also increases the risk of BCCs in their 30’s and 40’s, however, the mechanism is poorly understood. Rombo syndrome is associated with vermiculate atrophoderma, milia, trichoepitheliomas, and hypotrichosis.

- Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome is an X-linked dominant disorder where individuals develop congenital hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, milia, as well as numerous BCCs.

- Xeroderma pigmentosum individuals develop BCCs at about nine years of age. The condition is autosomal recessive and impairs DNA repair due to UV damage. They also suffer from sensitivity to light, premature ageing, and mottled pigmentation.

- Muir-Torre syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder affecting DNA mismatch repair genes that can result in several different types of cancer including BCCs and cancers of the bowel, genitals, urinary tract, and sebaceous glands.

Immunosuppression

Those who are chronically immunosuppressed have an increased risk of developing a BCC. The risk increase differs for the various types of immunosuppression but is in the range of a 2-7 times risk. Common causes of immunosuppression include medication for transplant recipients, autoimmune diseases as well as long-term HIV-positive patients.

Alcohol

Alcohol has been shown to be associated with a small increased risk of about 7% for every unit per day consumed. For example, if on average you drink 14 units of alcohol per week then this is associated with a 14% higher risk of BCC compared to non-drinkers.

How does a basal cell carcinoma develop (Pathogenesis)?

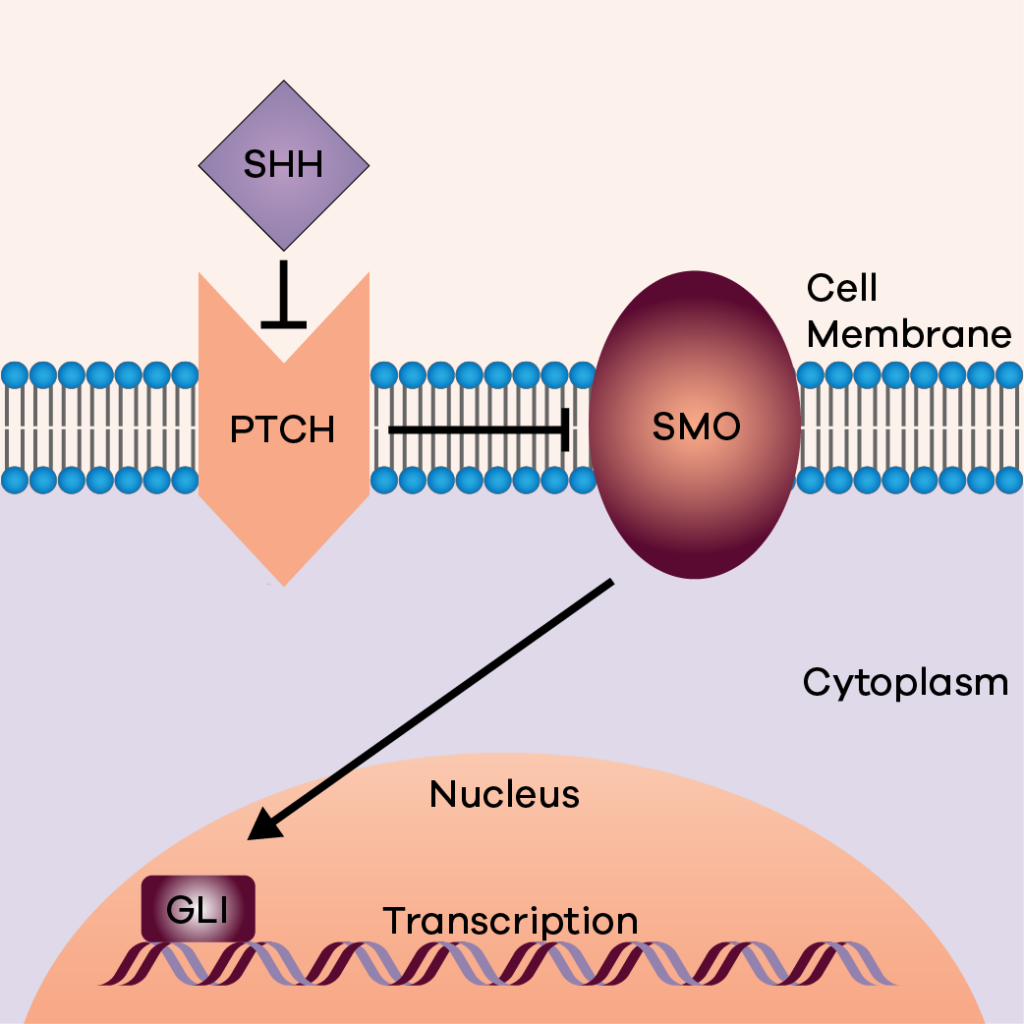

BCCs develop from a complex interaction of genes and environmental influences, in particular UV-induced DNA damage. Until relatively recently, the development of BCCs was a mystery. However, in the mid-1990s scientists discovered the aberrant function of the hedgehog signalling pathway leading to uncontrolled growth of cells and BCC. It is thought that 90% of BCCs have mutations in the hedgehog signalling pathway. Subsequently, several other signalling pathways have been found to be associated with the development of BCCs, including mTOR, NOTCH, Hippo, and WNT. Some of these pathways are being studied by pharmaceutical companies in an attempt to develop medications to treat BCCs.

The sonic hedgehog signalling pathway. SHH ligand binds and inhibits PTCH protein with stops the suppression of SMO activating the GLI transcription.

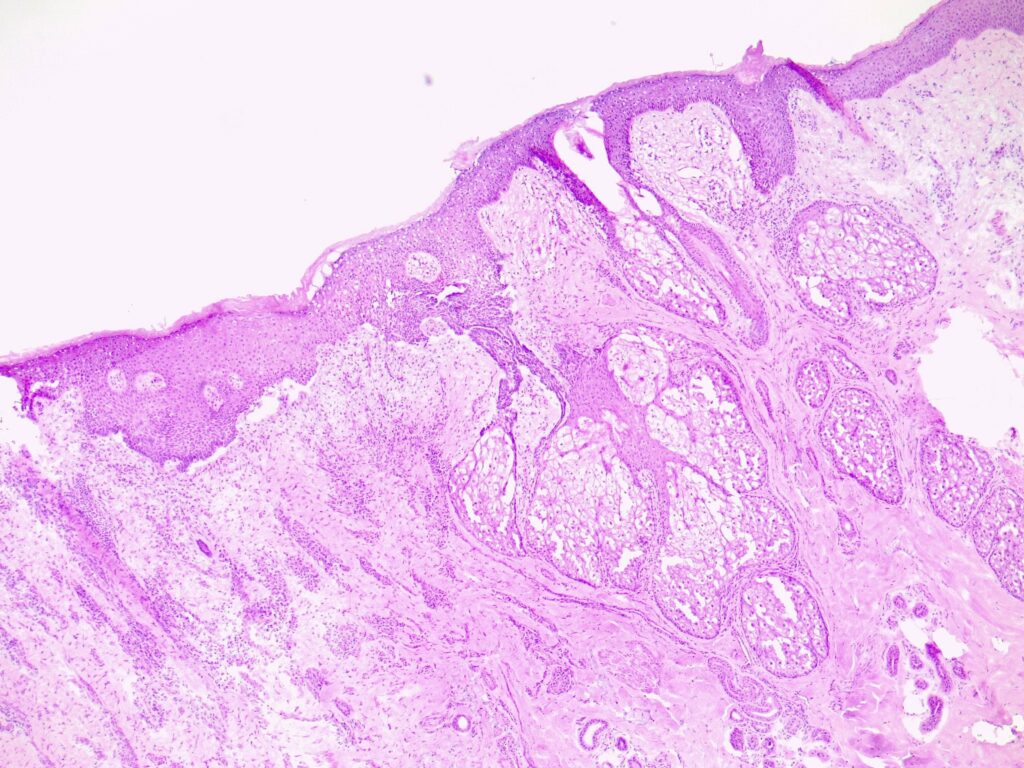

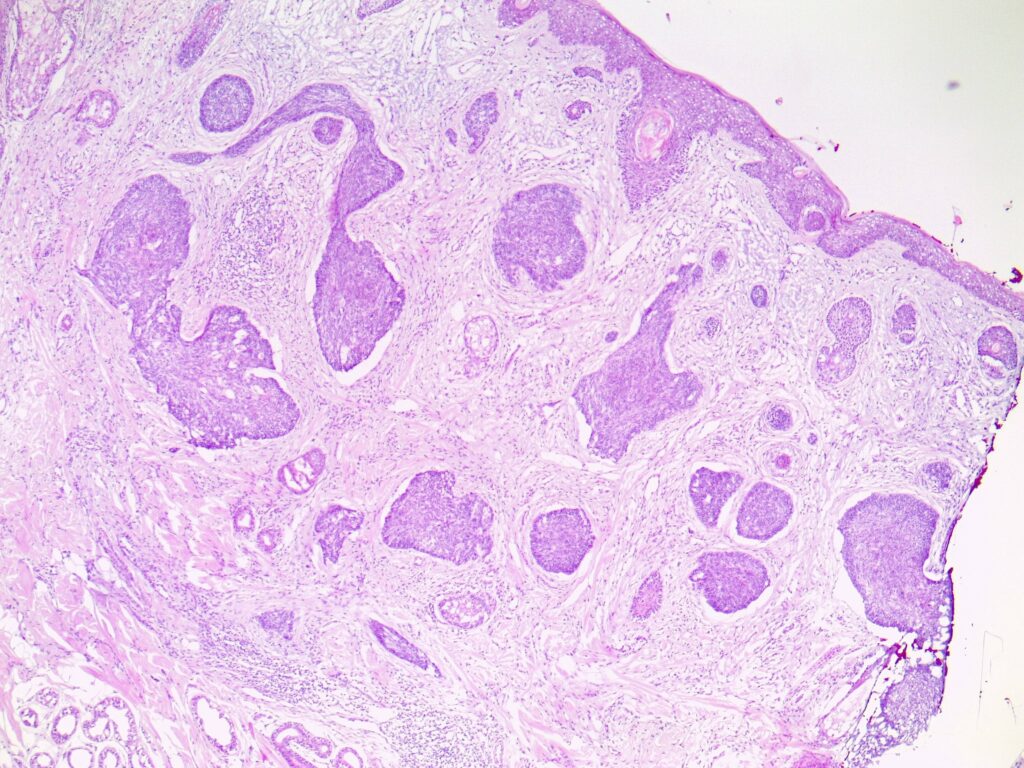

Subtypes of BCC

While there are several different subtypes of BCC, around 40% of tumours have features of two or more types:

- Superficial describes a pattern that grows superficially while budding off the basal layer of the epidermis.

- Nodular BCCs are the most common, making up about 80% of all BCCs. They form nodules/clumps of it within the skin and can extend to the subcutaneous tissue.

- Pigmented BCCs contain areas of melanin (skin pigment).

Aggressive subtypes:

- Micronodular BCCs form nodules but are organised into much smaller nests than nodular BCCs.

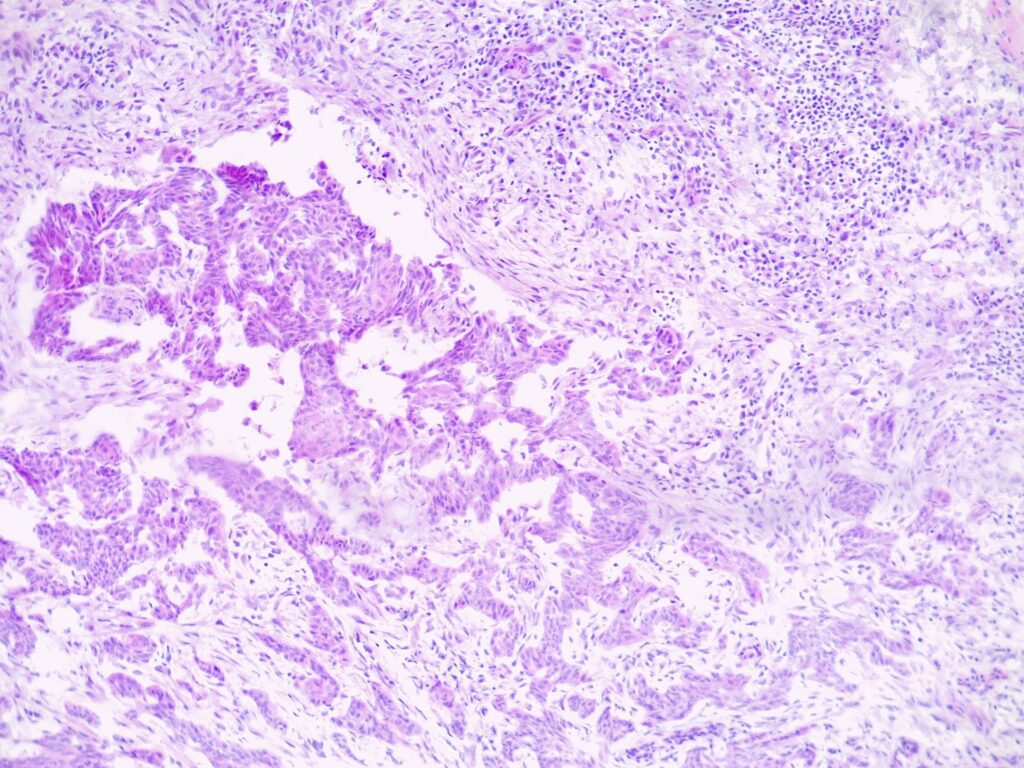

- Infiltrative BCCs form numerous small strands and cords of BCCs through the tissue.

- Basosquamous contains features of BCC and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Clinical Features (Symptoms & Appearance)

BCCs usually present as slowly growing, flesh-coloured lesions, although a minority can contain pigment or dark areas. They can ulcerate and cause repeated bleeding with minimal trauma or even spontaneously. Sometimes they can cause irritation or itch.

The different subtypes have different appearances:

- Nodular BCCs typically present as an obvious rounded lump.

- Infiltrative or morphoeic BCCs can present as a subtle, slight texture change on the skin that can be difficult to detect. As a result, they are often missed on skin checks.

- Superficial BCCs typically get confused with eczema or fungal infections.

Adjusted for surface area, the face, head, and neck is the most common site for BCCs, followed by the trunk.

How is a basal cell carcinoma diagnosed?

Most of the time an experienced dermatologist will be able to diagnose BCCs clinically (without a biopsy). Because dermatologists who specialise in skin cancer are seeing thousands of BCCs per year, it becomes a form of pattern recognition or ‘instinctive’. However, there are always times when a biopsy is required to ensure the correct diagnosis.

There are many types of biopsies that can be performed. The key is to obtain an adequate tissue sample that is representative of the lesion so that the laboratory can confirm the diagnosis and provide adequate information to make treatment decisions, e.g. depth, how aggressive it is, etc.

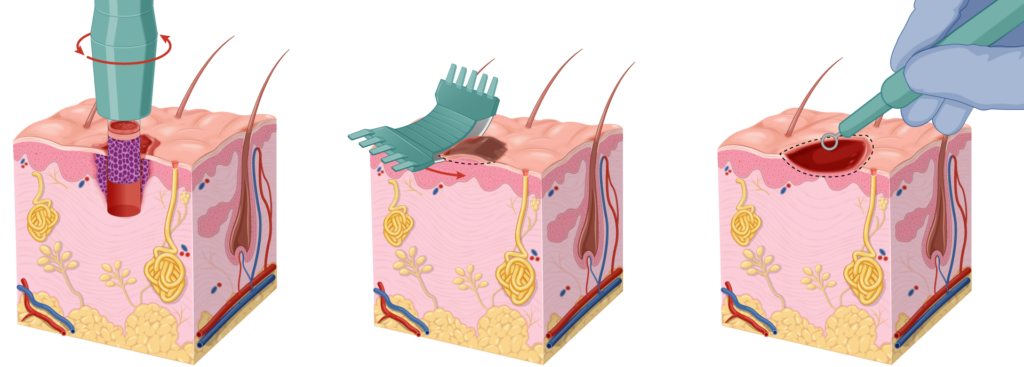

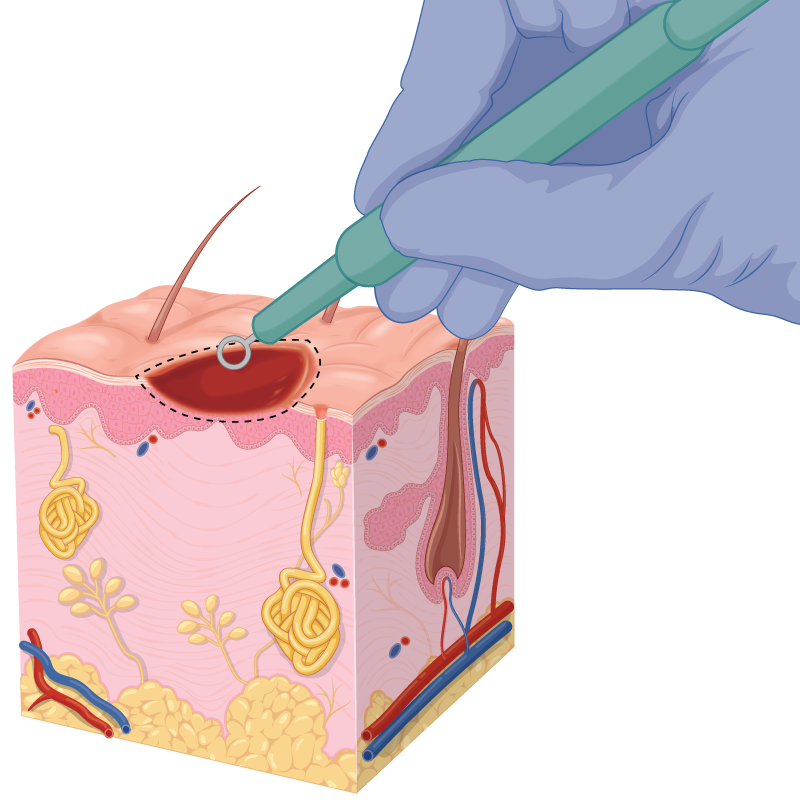

- A Punch biopsy is the gold standard, however, it will normally require stitches meaning that you will need to rest and look after the wound. You will need to return to the clinic a week later for stitches to be removed which is often inconvenient for people. There is also a risk of bleeding with this type of biopsy.

- A shave or a curettage biopsy is an alternative option, provided the doctor takes care to obtain an adequate sample for the laboratory. The advantage of this biopsy is that it is superficial, often requires no rest period and patients don’t need to return to the clinic for removal of stitches.

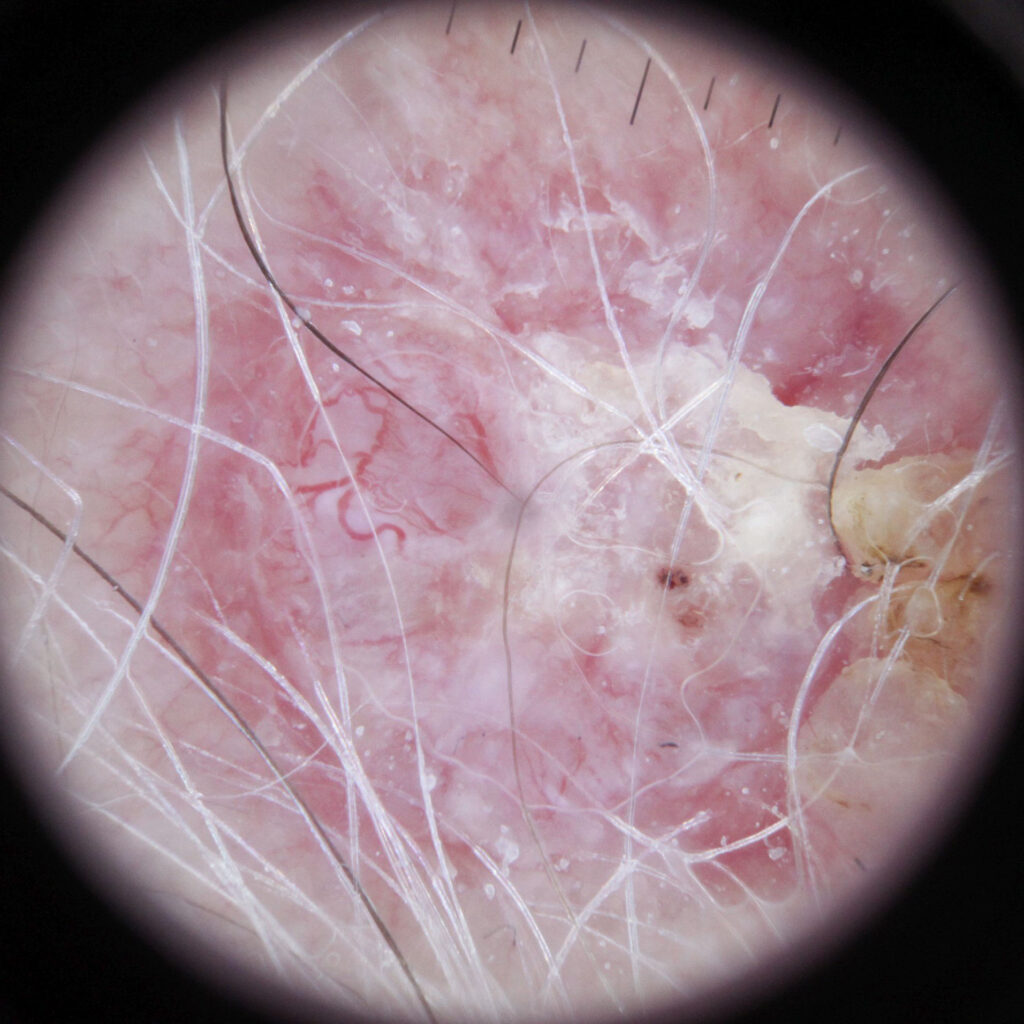

Dermoscopy can assist the dermatologist to make a diagnosis

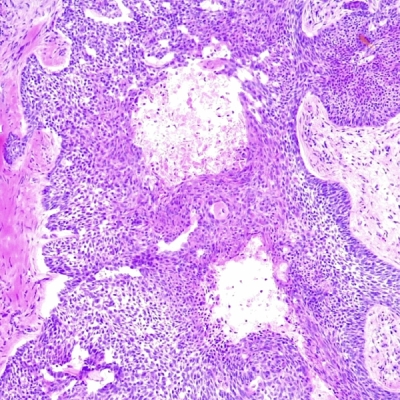

Once obtained, the sample is fixed in formalin, stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and prepared on slides. The pathologist will then examine these slides under a microscope and issue their report.

Treatment of a basal cell carcinoma

Treatment planning is undertaken in conjunction with your doctor and will take into consideration a number of factors. These include the depth, size, location, and stage of the BCC as well as your personal preference. Your life situation may also come into consideration.

Depth

A critical decision is whether it can be suitably treated by non-invasive methods or whether surgery is required. The critical assessment is the depth of the BCC. Unfortunately, this is not straightforward for superficial BCCs as it is not a simple matter of reading the histology report. For instance, a histology report may state that the BCC is superficial, but it could still have areas of invasion deeper into the dermis. It is possible that the biopsy was taken from an area of the cancer. This is not representative of a more advanced BCC. Experienced doctors will minimise this risk.

Your doctor will need to determine whether there are any clues of a deeper invasion:

- This could be stated in the histology report.

- There may be subtly raised areas in the BCC.

- There may be areas of significant erosion or ulceration suggesting deeper involvement.

If it is truly superficial then non-invasive treatments could include imiquimod cream or cryotherapy. It is important to realise that there is still a higher risk of recurrence. Furthermore, some of these treatments can cause scarring or hypopigmentation over large areas. Consideration also needs to be given to the consequences of recurrence e.g., in high-risk sites or cosmetically sensitive areas. When a BCC recurs, it tends to be larger and the treatment more complicated.

The cure rates for non-invasive treatments when used for superficial BCC are approximately:

- Imiquimod (Aldara) cream 80%.

- Photodynamic therapy (PDT) 73%.

- Fluorouracil (Efudix) cream 80%.

- Cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen) 90%.

Of course, the efficacy of the topical (cream) treatments will be heavily influenced by how well that patient adheres to the prescribed regimen. If compliance is expected to be poor, then other treatments should be recommended.

Curettage and Cautery

Curettage and cautery is a quick, minimally invasive surgical procedure that can be thought of as superficially ‘scraping’ the cancer. However, it is not possible to perform tissue analysis to confirm the complete removal of the BCC.

Furthermore, cure rates are variable and can be as low as 80%. It also generally results in a poor cosmetic outcome – commonly resulting in broad, white, and depressed scars. Nonetheless, it may be a preferred option for older patients who are unconcerned about cosmesis or recurrence in their expected lifetime.

Surgery

For most BCCs, surgical excision is recommended. The two main surgical techniques are wide local excision (WLE) and Mohs surgery. Surgery is normally performed under local anaesthetic and requires care for a stitched wound.

A WLE is a reasonable option for low-risk BCCs on the trunk or limbs. We discuss WLEs in more detail on our skin cancer removal page. The recurrence rate for WLE is approximately 5-15% however, this is dependent on:

- The subtype, as a more aggressive subtype, has a higher recurrence rate.

- The tumour’s location and size.

- The surgeon’s incomplete excision rate. We have a page dedicated to why this is important here.

- A range of less significant risk factors.

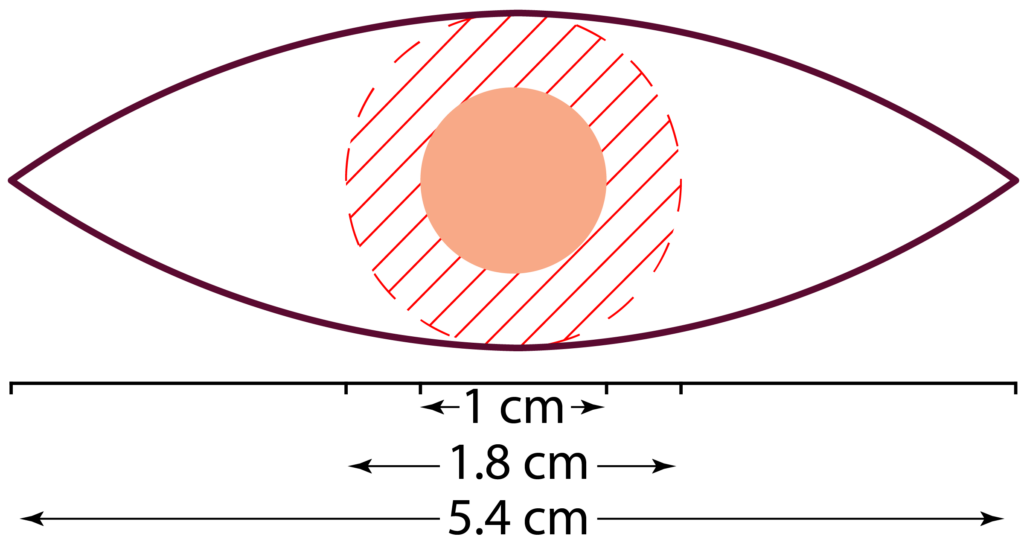

Plan of elliptical excision with 4 mm surgical margins for a 10 mm lesion. This plan can result in a 5.4 cm scar line.

A wide local excision (WLE) is normally performed under local anaesthetic. The surgeon marks out the lesion based on their visual inspection. A 4-5 mm margin is standard for BCCs, but may be larger for high-risk BCCs. The incision will be made in a 3:1 ellipse around this safety margin. A BCC with a 1 cm diameter will result in a scar line approximately 5.5 cm long (on cylindrical areas e.g., the arm, the ratio may be 5:1, meaning a scar line of about 9 cm).

Mohs Surgery

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is the gold standard treatment for BCCs of the head, neck, digits, and genitals, especially lesions that are considered higher risk. Mohs can also be used on the trunk or limbs for difficult, high-risk or recurrent BCCs. Mohs surgery has a recurrence rate of 1% for most lesions, however, it is around 2% or higher for high-risk lesions.

Mohs surgery has some key advantages:

- It keeps the surgical defect and wound as small as possible – this is particularly important in cosmetically sensitive areas. If you have a BCC on the tip of the nose, a bigger wound can have a significant cosmetic impact.

- Specimen (histological) analysis is undertaken while you wait. This means you don’t need to return at a later date for further surgery as it is all sorted out on the same day.

- Higher cure rate compared to standard surgery (WLE).

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is an alternative option to surgery for those who are unable to tolerate a surgical procedure. The radiation is delivered over a course of treatment, requiring multiple trips to the hospital. The cure rate for radiotherapy is about 92% for previously untreated BCCs.

Unfortunately, radiotherapy tends to have worse cosmetic outcomes compared to surgery as radiotherapy fields tend to degrade over time.

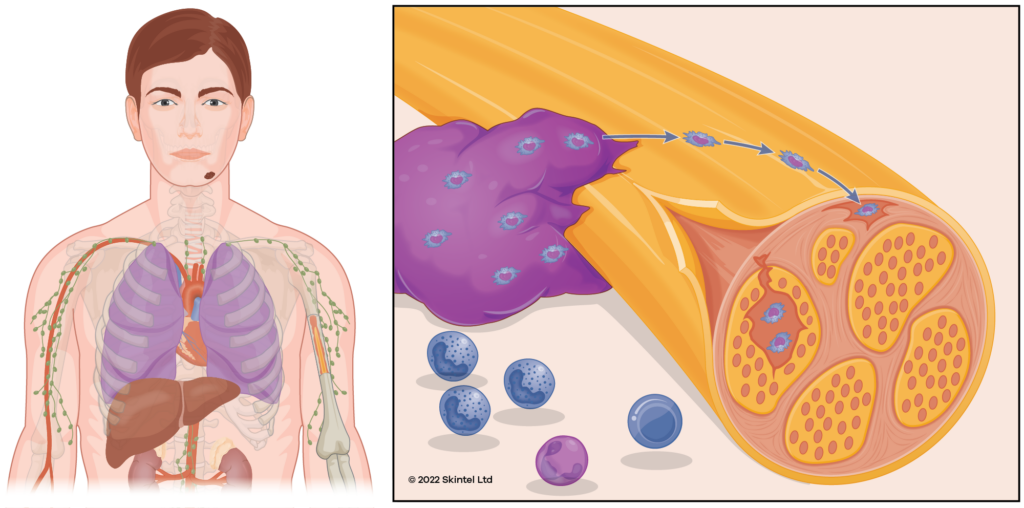

Radiotherapy may be used as an adjunct to surgery where the tumour was unable to be completely removed or for high-risk lesions to reduce the risk of future recurrence. It is particularly used in tumours with significant perineural invasion (when the cancer is starting to track around nerve fibres).

Recurrent tumours

It is important not to keep treating the BCC with the same treatment modality if the tumour recurs and alternative options are available. For example, if it recurs after treatment with cryotherapy or imiquimod, the doctor needs to consider whether this was an appropriate treatment for this tumour in the first place and whether the BCC was invading deeper than what was assumed. In the case of recurrence after non-invasive treatments, strong consideration should be given to further treatment with surgical approaches.

Advanced stage BCCs

If it is no longer localised to the skin and subcutaneous tissue, treatment will be more complex and is often undertaken in the context of a multidisciplinary team (MDT). Further investigations may be required (e.g., CT/MRI scans) to determine what structures (eg. nerves, muscle, bone) are involved which will guide further treatment.

Surgery is still often used, however, advanced BCCs may require a general anaesthetic to remove with complex surgery. Surgery may be followed by radiotherapy and systemic treatments such as hedgehog pathway inhibitors (vismodegib, sonidegib) or checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy (PD-1 inhibitor: cemiplimab).

Prognosis & complications of a basal cell carcinoma

If left untreated, BCCs will start to break down into a chronic wound causing recurrent bleeding or ooze requiring regular dressings. They can cause problems by invading adjacent structures (bones, muscles, etc) or by travelling down nerves (perineural invasion). It is rare for BCCs to spread (metastasise) to other areas of the body. BCCs can recur after treatment, often over a larger area than the original.

It is common for people to develop further new BCCs:

- About 45% of people will develop another one within five years of a BCC diagnosis.

- Those with two previous BCCs have a 75% chance of developing another within 5 years.

As a result, we recommend regular skin checks at least every twelve months after being diagnosed with a BCC.

Prevention of basal cell carcinoma

The main approach to prevention involves sun protection. Some studies have suggested that rigorous sun protection during childhood can reduce the development of BCCs by 78% but this level of reduction has not yet been conclusively proven.

Obviously, daily sunscreen use requires a significant commitment from people – even dermatologists are not perfect with their sun protection.

General sun protection advice includes:

- Avoid sunburn and intentional tanning.

- Wear sun protective clothing – hat, sunglasses.

- Seek shade where available.

- Extra care needs to be taken in highly reflective environments e.g., water, snow, sand.

- Vitamin D should be obtained through food and supplements.

- Broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen with a minimum of SPF50.

We have separate pages dedicated to sun protection and sunscreen. These pages cover controversial topics such as the impact on vitamin D, high-SPF sunscreens, and the systemic absorption of sunscreen ingredients.

Some studies have suggested that the use of nicotinamide (vitamin B3) may help reduce the risk of developing BCCs by 20%. Unfortunately, subsequent analysis has called into question the validity of these studies. Further studies are required to establish the efficacy of nicotinamide.

Other Resources

- DermNet NZ:

- Other sites:

References

- Dubas LE, Ingraffea A (2013). Nonmelanoma skin cancer. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 21 (1): 43-53. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2012.10.003

- Gandhi SA, Kampp J (November 2015). “Skin Cancer Epidemiology, Detection, and Management”. The Medical Clinics of North America. 99 (6): 1323-35. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.06.002

- Staples MP, Elwood M, Burton RC, Williams JL, Marks R, Giles GG. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Australia: the 2002 national survey and trends since 1985. Med J Aust. 2006;184(1):6-10. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00086.x

- Abroms L, Jorgensen CM, Southwell BG, et al. Gender differences in young adults’ beliefs about sunscreen use. Health Educ Behav. 2003 Feb;30(1):29-43. doi: 10.1177/1090198102239257

- McCarthy, W. H. (2004). The Australian experience in sun protection and screening for melanoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 86(4), 236-245. doi: 10.1002/jso.20086

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case-case-control study. Br J Cancer 2006; 94:743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602982

- Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. I. Basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 1995; 131:157. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690140041006

- Kricker A, Armstrong BK, English DR, Heenan PJ. Does intermittent sun exposure cause basal cell carcinoma? A case-control study in Western Australia. Int J Cancer 1995; 60:489. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600411

- Karagas MR, Zens MS, Li Z, et al. Early-onset basal cell carcinoma and indoor tanning: a population-based study. Pediatrics 2014; 134:e4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3559

- George EA, Baranwal N, Kang JH, et al. Photosensitizing Medications and Skin Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel) 2021; 13. doi: 10.3390/cancers13102344

- Watt TC, Inskip PD, Stratton K, et al. Radiation-related risk of basal cell carcinoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104:1240. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs298

- Kishikawa M, Koyama K, Iseki M, et al. Histologic characteristics of skin cancer in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: background incidence and radiation effects. Int J Cancer 2005; 117:363. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21156

- Khalesi M, Whiteman DC, Tran B, et al. A meta-analysis of pigmentary characteristics, sun sensitivity, freckling and melanocytic nevi and risk of basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Epidemiol 2013; 37:534. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.05.008

- Wehner MR, Linos E, Parvataneni R, et al. Timing of subsequent new tumors in patients who present with basal cell carcinoma or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151:382. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3307

- Dubas LE, Ingraffea A (2013). Nonmelanoma skin cancer. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 21 (1): 43-53. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2012.10.003

- Youl, P. H., Janda, M., Aitken, J. F., Del Mar, C. B., Whiteman, D. C., & Baade, P. D. (2011). Body-site distribution of skin cancer, pre-malignant and common benign pigmented lesions excised in general practice. British Journal of Dermatology, 165(1), 35-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10337.x

- Bath-Hextall F, Ozolins M, Armstrong SJ, et al. Surgical excision versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal-cell carcinoma (SINS): a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15:96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70530-8

- Arits AH, Mosterd K, Essers BA, et al. Photodynamic therapy versus topical imiquimod versus topical fluorouracil for treatment of superficial basal-cell carcinoma: a single blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14:647. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13460

- Hall VL, Leppard BJ, McGill J, Kesseler ME, White JE, Goodwin P. Treatment of basal-cell carcinoma: comparison of radiotherapy and cryotherapy. Clin Radiol 1986 Jan;37(1):33-4 doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(86)80161-1

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1989 Mar;15(3):315-28 doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1989.tb03166.x

- Thissen MR, Neumann MH, Schouten LJ. A systematic review of treatment modalities for primary basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135:1177. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.10.1177

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1989; 15:315. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1989.tb03166.x

- Robinson JK. Risk of developing another basal cell carcinoma. A 5-year prospective study. Cancer 1987; 60:118. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870701)60:1<118::aid-cncr2820600122>3.0.co;2-1

- Karagas MR, Stukel TA, Greenberg ER, et al. Risk of subsequent basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin among patients with prior skin cancer. Skin Cancer Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1992; 267:3305. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480240067036

- Wehner MR, Linos E, Parvataneni R, et al. Timing of subsequent new tumors in patients who present with basal cell carcinoma or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151:382. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3307

- Stern RS, Weinstein MC, Baker SG. Risk reduction for nonmelanoma skin cancer with childhood sunscreen use. Arch Dermatol 1986; 122:537. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1986.01660170067022

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

Related Posts

-

Does Nicotinamide Help with Skin Cancer?

An in-depth review of the evidence for and against supplementing with nicotinamide in an effort to reduce the risk of developing skin cancer.Read more

-

What a Mohs Surgeon sees under the Microscope

Experience matters when it comes to picking out a tumour under the microscope. The Skintel Mohs specialists have viewed more than 10,000 slides and counting! […]Read more

-

Skin Cancer: A Basic Guide

Skin cancer is by far the most common type of cancer. They are most common in areas with lots of sun exposure such as the face, neck, arms, and head.Read more